–¬º”∆¬¡˘∫œ≤ ø™Ω±÷±≤• the author: Cathy Martin is –¬º”∆¬¡˘∫œ≤ ø™Ω±÷±≤•'s director of Indigenous community engagement. You can read more about her in this recent Dal News feature.

In 1996, June 21 was declared in Canada. In 2009, 13 years later, the month of June was declared National Indigenous History Month, . This provides an opportunity to recognize not only the historic contributions of Indigenous peoples to the development of Canada, but also the strength of present-day Indigenous communities and their promise for the future.

While it was only recently declared a national Indigenous history month by the Canadian Government, it has been a significant time of celebration for Mi‚Äôkmaq for over the past 14,000 years. ¬Ý

For the Mi’kmaq, June 21 is a time of renewal: the coming of summer, the summer solstice, the longest day of the year and shortest night, time for planting in conjunction with the new moon. It is the month of the Strawberry moon when the little wild strawberries are blooming. The English words for the months are based on the Gregorian Calendar. Mi’kmaw language names are descriptive and offer us information on the order of things to maintain our way of life. Nipnikús is the name of this time, which translates to “Leaves Full Blossom” or “Leaves are Budding Time.”

The importance of history

For thousands of years we have lived in harmony with the earth, with all creation. It has only in the past 500 or more years that we as Mi’kmaq and Indigenous peoples of Canada have had to live and tolerate the imposed values system of a culture from another land, Europe. A culture that has not respected the way of life of the original people of this land. A culture that had not lived in harmony with the land and creation.

My longtime friend and colleague, Patricia Doyle Bedwell — professor in the College of Continuing Education, and Dal’s first tenured Mi’kmaw faculty member — shared her thoughts about the significance of this month:

‚ÄúLearning about Indigenous People's history¬Ýhelps all Canadians to understand our shared experiences. Understanding the past acknowledges the impact on the present. We, as Mi'kmaw people, have a nation to nation relationship with the Crown. The Mi'kmaq signed the Covenant Chain of Treaties with the British Crown (1725-1761) that received recognition of the Supreme Court of Canada in 1985 and 1999. That sets the parameters of the relationship.‚Äù

During this time, Nipnik’us (June), the Canadian government declares “…it is a time for learning about, appreciating and acknowledging the contributions First Nations, Inuit and Métis people have made in shaping Canada. The Government of Canada recognizes the importance and sacred nature of cultural ceremonies and celebrations that usually occur during this time.”

Read also: Recognizing Indigenous History Month

What is there to celebrate? Have Canadians learned about and celebrated our contributions yet? Who is celebrating? The Indigenous people or the new Canadians, the British, immigrants to our land?

Professor Bedwell’s offered some response to my questions.

‚ÄúCanadians have not learned Indigenous history yet Indigenous peoples played a pivotal role in the creation of Canada. As Elders taught us, we must learn the past to understand the present and where we are going in the future. Canada's treatment of Indigenous peoples such as forced assimilation, residential schools and outlawing of our spiritual ceremonies imposed cultural genocide against our peoples. Canadian policies came from systemic racism and sexism against Indigenous peoples. Government denied our humanity.‚Äù¬Ý ¬Ý

What we celebrate

Why is it important to celebrate ceremonies of the Mi’kmaq in this country when it is part of the rights and freedoms of all Canadians under the constitution?

We celebrate this freedom because for hundreds of years, we were denied this right in accordance with the Canadian government‚Äôs Indian Act (1876). We celebrate the right to vote, which was denied Indigenous peoples of Canada until the 1960s. We celebrate the fact that our children are no longer in residential schools and are free to live with their own families and speak their own language without fear of punishment. We celebrate the fact that women who marry outside of our Indigenous race are not stripped of the right to be Indigenous. We celebrate the thousands of graduates from secondary and post-secondary schools over the past50 years because we were denied this right to education previously. We celebrate our human rights today, because we never had our human rights recognized until 2008, even though the¬Ý Constitution Act 1982 was supposed to protect our rights. We celebrate that we, the Mi‚Äôkmaq, are still here and thriving. Above all, we celebrate the rising and setting of the sun each day in thanks for another day.

As elder Dr. Albert Marshall of Eskasoni suggests, we must look at things in a two-eyed seeing approach: Look at what both cultures have to offer, look through the Indigenous knowledge lens and the scientific lens. One needs to see one another’s perspective to see the whole picture.

Through my Indigenous lens, I try to see the good in the world, the positive side of things. However, this year, I am looking through my lens and it is very difficult to be optimistic and positive about what we have seen recently.

A hope as yet unanswered

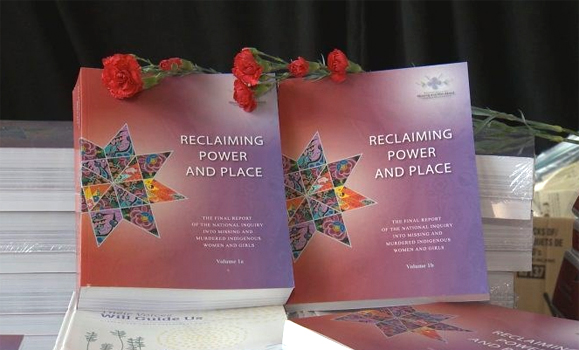

It has been one year since the release of the report on the findings from the national inquiry into (MMIWG). It has joined the ranks of numerous reports on inquiries and commissions over the decades, such as the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, The Calls to Action from The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the Marshall Report, among many others.

I attended the release of the MMIWG report that named Genocide of Indigenous Women as the finding from the two-year inquiry. The celebration at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in the Great Hall, which honours our heritage through its very design, was promising. My daughter was with me, as she had worked with the Eastern Door (four Native women associations from the Atlantic) and presented their submission to the inquiry. I was overwhelmed with emotion and pride as they offered a collective voice to the commission from the Wabanaki territory, the only submission from the East. That experience gave me a great sense of hope and optimism for the future generations to come.

On the other hand, the fact that we had to have a national inquiry in the first place due to the disproportionate number of MMIWG in Canada was demoralizing. The three-year experience of working with MMIWG families to put that submission together took a toll on many of us from this region. The stories and the injustices repeated over and over again by contributors were incomprehensible. A trillion-plus tears were shed during that time. It was empowering and at the same time horrifying. Our hopes were that this action plan from the recommendations would be in place within a year so that, today, we would be well on our way as a society to writing some of the wrongs and giving the victims and families some sense of hope and resolve.

What we can learn — and change — together

Over the past year since the release of the MMIWG report on findings, we have seen our fair share of violence and murder in our communities. That some of these crimes committed by people in authority who are supposed to protect us has been disillusioning. We saw the pandemic arrive and the world will never be the same, and not just from its challenges. We hope to take good things from this pandemic as well: the coming back of nature to places where it's been almost lost, the acknowledgement of climate change and pollution on our lives, our air and water. The outcries from mother earth have been heard.

During this important month, of celebration of our history, we are still reeling from the recent murders of 22 people in our territory by one man. We have watched a man be murdered by police in the US on the news, and the world change in response. It has opened up many eyes to the meaning of racism. In the last week, as we approach June 21st, the summer solstice — a time of renewal — we are walking in ceremony for two Indigenous people, a mother of one and a father of two, murdered at the hands of our police, our so-called protectors. We see the law not working in support of the people, as crimes by authorities in our country are being dismissed by the highest courts.

The silver lining in all of this tragedy is the many more people around the world are seeing and understanding more about the imbalance between races of people. The truths of the matters are right before our eyes, in clear daylight. It has brought together many races in solidarity. It has been a painful awakening for many. However, it has made the possibilities for change boundless.

While celebrations and events for National Indigenous History Month may be different this year than those in the past, we can still share and learn from stories, traditions and culture in new ways that keep us together and connected. However, to truly understand our present-day situation, one must learn about our past. The stories of resilience and survival, in our own homeland, have not been celebrated by all Canadians. The truth of our history since the arrival of British must be told, told by Indigenous people of this land, through our lens.

M’sit Nokomaq / All my relations.

Catherine Anne Martin, BA, MEd, CA

Director, Indigenous Community Engagement