The Early Days of Oceanography

At ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・

1959-1986

By: Donald Gordon

Emeritus Scientist

Department of Fisheries and Oceans

Bedford Institute of Oceanography

Dartmouth, NS

Donald.gordon@ns.sympatico.ca

December 21, 2021

ABSTRACT

In 1959, the Canadian Joint Committee on Oceanography recommended the creation of the Institute of Oceanography at ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ (IODal) in Halifax. Its mandate was to train the oceanographers needed for the rapidly expanding Canadian oceanographic effort and to conduct academic research in the marine sciences on the east coast and in the Arctic. It complemented a similar institute founded ten years earlier on the west coast at the University of British Columbia. Initial development of the Institute was led by F. Ronald Hayes who served as director for five years until he moved to Ottawa to become the Chair of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. He was replaced by Gordon A. Riley, an eminent biological oceanographer from Yale University.

Under his leadership, and with the unwavering support of President Henry Hicks, the Institute grew steadily in both personnel and program and in 1971 morphed into a full Department of Oceanography. This same year the Department moved into its own building in the new Life Sciences Centre. Gordon Riley stepped down as Director in 1974 but was followed by other directors who kept the ship firmly on course.

Over the years, the program developed in very close cooperation with the federal Bedford Institute of Oceanography located across the harbour in Dartmouth. This history documents some of the major achievements over the time period of 1959 to 1986 when the Institute was formally disbanded. During this period, the ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ oceanography program earned an outstanding international reputation that continues today.

DEDICATION

This history is dedicated to Gordon Arthur Riley who, in 1965, moved from the Bingham Oceanographic Laboratory at Yale University to ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ to become the Director of the fledgling Institute of Oceanography. Under his leadership, the Institute grew into the highly respected Department of Oceanography that continues to thrive today.

INTRODUCTION

During the summer of 1962, I had the good fortune to met both Peter Wangersky and Gordon Riley, then at Yale窶冱 Bingham Oceanographic Laboratory, while taking the marine ecology course at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, MA. As a young graduate student, I was most impressed with them both. That same year I also met Eric Mills, a graduate student at Yale who was working in the lab of Howard Sanders at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and auditing the MBL marine ecology course. Little did I know that six years later the three of them would be signing my PhD diploma in oceanography at ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・.

The following year, as a graduate student at the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island, I worked with Pete on a long cruise of the RV Trident to West Africa. We had many pleasant conversations together while sitting on deck watching the water go by. He answered my many questions about oceanography and I developed an interest in learning more about the vast pool of non-living organic matter in the ocean. At the end of the cruise, Pete urged me to consider coming to Yale to pursue a PhD under Gordon after I finished my master窶冱 degree in benthic ecology. Gordon was most agreeable to this possibility and so I applied to Yale.

Unfortunately, I was not accepted. Gordon was upset because he never had the opportunity to comment on my application. This was just one of many things he was unhappy with at Yale. Soon after he informed me that he was considering leaving Yale and was actively pursuing other possibilities. In November 1964, I visited him in New Haven and he told me he had just accepted the position as Director of the ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ Institute of Oceanography (IODal) and urged me to apply. My first question was where is ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・? I knew very little about Nova Scotia but figured it would be an interesting place to spend three years doing a PhD under Gordon窶冱 tutelage. I subsequently applied, was accepted and moved to Halifax in September 1965 soon after Gordon arrived. Pete Wangersky had also resigned from his Yale position and moved to IODal at the same time.

My three years as a graduate student at IODal were a marvellous experience. I learned much, met many wonderful people who became lifelong friends and fell in love with Nova Scotia. After finishing my doctorate and getting married in 1968, both in the same week, the next step in my career was a faculty position in the Department of Oceanography at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu. However, my wife Joleen and I wanted to return to Nova Scotia as soon as a suitable job opened up at either ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ or the Bedford Institute of Oceanography (BIO). We were delighted to return two years later from our extended honeymoon in Hawaii when, at the invitation of Lloyd Dickie, I joined the Marine Ecology Laboratory (MEL) at BIO where I was privileged to enjoy a long and satisfying career as a research scientist and program manager.

Having a long-standing interest in history, I spent much of the time at home during the COVID-19 pandemic preparing a history of MEL (Gordon 2021a and b). Upon its completion, while the pandemic continued and I still had some gas left in the tank, I decided that my next major writing project would be preparing a similar history of the ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ Institute of Oceanography (IODal).

This account is a labour of love that I hope accurately chronicles the history of IODal and its many contributions to training new oceanographers and advancing our knowledge of the oceans. It covers the time period beginning with its creation in 1959 to when it ceased to exist on paper in 1986 when the last annual report was issued. The focus is on the early years before the Department of Oceanography was created in 1971. It begins by reviewing the origins of IODal. After describing its structure and operation, it reviews the year-by-year evolution of its faculty, students and programs. Also included are some representative research highlights of faculty and graduate students. It then concludes with a brief summary. Further details are provided in appendices which include advisory committees, directors, faculty and students, student theses and graduates who were employed at BIO.

The information included in this history came from a variety of sources, the most important being the annual/biennial reports which were faithfully produced on a regular basis. Another major source was Gordon Riley窶冱 unpublished memoirs. Other information was gleaned from a 1967 pamphlet describing IODal, the scientific literature, the Internet, and numerous colleagues as well as my own personal memories.

The immediate target audience for this history is the many colleagues who were part of IODal and are still with us today. I hope that this account brings back an abundance of pleasant memories. In addition, I hope that it will be of interest to the broader oceanographic community as well as those interested in the history of ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・.

ORIGIN

The early development of Canadian marine science, including the events that led to the creation of IODal, has been reviewed by Mills (2014). Before World War II, oceanography in Canada, including physical oceanography, marine biology and fishery biology, was done entirely by the federal government under the Fisheries Research Board of Canada (FRB) at the St. Andrews Biological Station in New Brunswick and the Pacific Biological Station at Nanaimo in British Columbia. Soon after the war began, increasing attention was paid to physical oceanographic research because of the threat of German submarines and acoustic mines to North Atlantic shipping. In 1944, two new federal organizations were created under the FRB to conduct oceanographic research. On the east coast, the Atlantic Oceanographic Group (AOG) was established at the St. Andrews Biological Station and headed by Harry Hachey while, on the west coast, the Pacific Oceanographic Group (POG) was established at the Pacific Biological Station and headed by Jack Tully.

The mandate of AOG was to study the ocean environment and its dynamics taking into account the processes which maintain or modify ocean conditions in both inshore and offshore waters. The initial focus was on physical oceanography but soon expanded to include geology, chemistry and biology with strong links to fisheries. The geographic area of interest to AOG was initially the continental shelf of Atlantic Canada but later it expanded to include offshore waters and the Arctic. Ship time was provided by the Royal Canadian Navy, in particular the CNAV Sackville.

By the end of the war, in addition to AOG and POG, the National Research Council (NRC), Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), Defence Research Board (DRB) and several Canadian universities were expanding into ocean science. The need for national program coordination was recognized which led to the creation in 1946 of the Joint Committee on Oceanography (JCO). The JCO was composed of representatives from federal agencies and universities and was charged with coordinating the development of oceanography in Canada and allocating federal resources. Harry Hachey, then the Chief Oceanographer of Canada, was appointed as Chair.

As the various laboratories grew and research programs expanded, there were still few oceanographers and sources of trained personnel in Canada. Training new but inexperienced staff took time and as a result more experienced staff were frequently recruited from outside Canada. It was soon recognized that there was a critical need to establish a training program for oceanographers in Canadian universities. It was proposed that an institute of oceanography be created somewhere in the country and the University of British Columbia (UBC), McGill and ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ expressed interest in hosting such an institute (Mills 1994). After considering many factors, the JCO selected UBC in Vancouver as the site for such an institute because of its location, facilities and proximity to the Pacific Biological Station. Subsequently, the UBC Institute of Oceanography (IOUBC) was created in 1949. Well supported, IOUBC began a ten-year period as the only Canadian university training oceanographers. Its curriculum focused on physical and chemical oceanography and many of the first students were government scientists looking to upgrade their professional qualifications. However, soon after IOUBC was established, under the lead of F. Ronald Hayes, ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ began to lobby for the creation of a similar institute on the east coast, this one focusing on marine bacteriology (Mills 1994). Initially, it was not successful in convincing the JCO of the need for a second academic institute in Canada but conditions later changed and the Institute of Oceanography at ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ (IODal) was thereby created in 1959 with Ron Hayes as Director.

Also in 1959, the JCO was reorganized and expanded to include the University of British Columbia (UBC), the University of Toronto and ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ and was renamed the Canadian Committee on Oceanography (CCO). William van Steenburgh of the Department of Mines and Technical Surveys was appointed Chair and Harry Hachey served as Secretary. Its mandate was to coordinate and direct work in oceanography and to represent the Canadian government internationally in the field of oceanographic research.

INITIAL OBJECTIVES, POLICY AND ORGANIZATION

The main objectives of the new Institute were to train the oceanographers needed for the rapidly expanding Canadian oceanographic effort and to serve as an academic research centre for advanced studies in the marine sciences on the east coast and Arctic. The Institute, through the University, would award the degrees of MSc and PhD in oceanography.

Two bodies were created to oversee the creation of IODal and the development of its program in the early years. A Board of Directors, chaired by the ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ president was composed of senior university administrators. Ron Hayes served as secretary. A Scientific Advisory Committee, chaired by Ron Hayes, who also chaired the ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ Biology Department, was made up of representatives from University of British Columbia, the University of Toronto, the Marine Sciences Branch (Ottawa), the Fisheries Research Board (Ottawa), the Naval Research Establishment (Dartmouth), the Nova Scotia Research Foundation, as well as the chairs of the ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・ departments of chemistry, geology and physics. The composition of the Board of Directors never changed but there were some changes in the composition and membership on the Scientific Advisory Committee (Appendix 1). Both these bodies were not included in the annual reports after 1968 so presumably they had been disbanded by that time when the Institute was firmly established and could run itself.

From the very beginning, the policy was to integrate the new institute into the broader educational program of ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・. In setting up the academic program, it was recognized that formal instruction in oceanography was essentially limited to the graduate level. The multidisciplinary nature of oceanography required a broad scientific background combined with specialized training in one or more of the basic disciplines. Graduate students were expected to combine oceanographic training with further studies in the basic sciences which were pertinent to their field of speciality. Participation in field courses, cruises and seminars would be required.

It was decided that IODal would offer an introductory class in basic oceanography and a series of advanced classes in specialized subjects. Graduate students working toward both the MSc and PhD degrees were required to take the introductory course and at least one advanced class. They were also expected to take courses in basic sciences which were relevant to their field of specialty. Doctoral students were also required to take an oral comprehensive exam and demonstrate reading proficiency in two foreign languages. However, in general the emphasis was on thesis research and the acquisition of an adequate academic background for future careers. The amount and kind of course work were decided individually according to the particular needs of the student. It was agreed that the advanced courses must be accepted by the basic science departments and open to their honours and graduate students with the hope that the Institute and departments would strengthen each other.

Funding was initially provided by an institutional grant from the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and university funds. With time, this expanded to include research grants obtained by staff from several federal agencies in both Canada and the US. Also, some students arrived with their own funding such as NRC studentships.

The geographic area of particular interest to the new Institute was envisioned to be the Northwest Atlantic Ocean including offshore waters, the continental shelf, major bays such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Bay of Fundy and coastal waters. While the initial focus was on biology, it was hoped that with time research programs could be established in all the basic oceanographic disciplines. The Institute was most fortunate that there was a commitment by federal agencies to provide ship time at no cost so there was no need to acquire and operate a research vessel. It was also recognized that it would be prudent to develop a close working relationship with other local scientific laboratories at the time with marine interest such as the Atlantic Oceanographic Group, the Naval Research Establishment, the FRB Fisheries Technological Station, the Atlantic Regional Laboratory of NRC and the Nova Scotia Research Foundation. BIO did not appear on the scene until 1962.

The initial faculty appointments were planned to be in marine zoology, bacteriology, chemistry, physics, geology and geophysics. All faculty members would also have departmental appointments and be physically located in their respective departments. Biologists were located in the Forrest Building, as was the IODal office. Chemists were located in the Chemistry Building and geologists and physicists were located in the Dunn Building.

An Admissions Committee was established and composed of the director and the heads of the four disciplinary departments. Incoming students were to be provided with a university stipend to cover all expenses. In exchange, they were required to serve as demonstrators in undergraduate labs in their respective departments.

EVOLUTION OF THE DALHOUSIE INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHY

(1959-1986)

1959

Members of the initial faculty were Ron Hayes (Director, Biology), Elmer (Tony) Anthony (Biology), John Teal (Biology) and Alan Mills (Chemistry). Physical oceanographic expertise was provided by three associates: Bob Stewart (Defence Research Board), Neil Campbell (Atlantic Oceanographic Group) and Ron Trites (Atlantic Oceanographic Group). The first graduate course offered was in physical oceanography and taught by Bob Stewart. Barbara Hendry was the administrative assistant.

From the very beginning, the policy was to integrate the new Institute into the

educational program of ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・. Academic staff would hold, as well as an Institute appointment, an attachment to the appropriate university department. Advanced oceanography courses must in general be accepted by one or more departments as having honours or graduate standing. In this way it was hoped that the Institute and departments would strengthen each other.

The faculty organized a speaking tour to Maritime universities to inform them of IODal and to encourage undergraduate students to consider a career in oceanography.

An NRC annual award of $90,000 was the major source of funding. Ship time was provided by federal agencies without cost.

Two students, Kevin Halcrow and Peter Hochachka, were admitted this first year, both in biology.

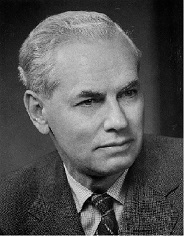

F. Ronald Hayes

Director 1959-1964

1960

The Scientific Advisory Committee met in June and reviewed the activities and plans. It was agreed that the entrance requirements were too rigid to accommodate applicants from a variety of university background training and tended to discriminate against students from outside ミツシモニツチマイハソェスアヨアイ・. Options were introduced into the entrance requirements so that students of high quality would not be rejected.

Dirk Nota (Geology), from the Netherlands, joined the faculty. The partnership with the Atlantic Oceanographic Group (AOG) was strengthened when it moved from St. Andrews to Halifax and Neil Campbell and Ron Trites took over teaching the physical oceanography course. Staff and students began to participate in field programs, thus initiating the long-standing tradition of Institute personnel working at sea.

Research highlights (including students and PDFs):

窶「 In cooperation with the Nova Scotia Research Foundation, a seismic refraction and reflection survey using a Cape Islander was carried out in the Northumberland Strait.

窶「 In conjunction with the RV Vema of the Lamont Geological Observatory, Columbia University, seismic refraction surveys were carried out using CNAV Sackville in the Labrador Sea and Gulf of St. Lawrence.

窶「 Phytoplankton productivity was measured using the C-14 method on an Arctic cruise aboard the CGS Labrador (Hayes).

Seven new graduate students were admitted in biology, chemistry and physics, including the first woman. One of these, Glen Geen, later transferred to the Department of Biology.